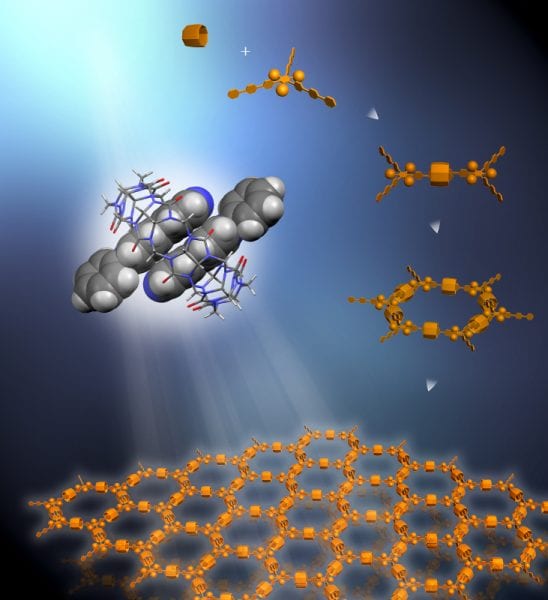

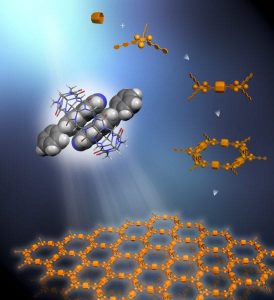

Rigid triangular struts self-assemble in combination with macrocycle rings in solution to create a supramolecular organic framework (SOF). Each strut contains functional units that resist stacking to maintain the 2D framework in a single layer.

Supramolecular chemistry, aka chemistry beyond the molecule, in which molecules and molecular complexes are held together by non-covalent bonds, is just beginning to come into its own with the emergence of nanotechnology. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are commanding much of the attention because of their appetite for greenhouse gases, but a new player has joined the field – supramolecular organic frameworks (SOFs). Researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have unveiled the first two-dimensional SOFs that self-assemble in solution, an important breakthrough that holds implications for sensing and separation technologies, energy sciences, and, perhaps most importantly, biomimetics.

“We’ve demonstrated the first soluble single-layer 2D honeycomb SOF that combines the ordering and porous features of MOFs with the solubility of supramolecular polymers,” says Yi Liu, a chemist with Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division and a corresponding author on the paper announcing the discovery. “The results prove that we can exercise precise control of dimensionality within structures through a solution-based supramolecular approach, which paves the way for the assembly of more advanced architectures that can be processed in solution.”

Traditional molecular chemistry involves the strong covalent bonds formed by the sharing or exchange of electrons between the atoms that make up a molecular system. Supramolecular chemistry involves systems that are held together by a multitude of weaker, non-covalent connections, such as hydrogen bonds and electrostatic and Van der Waals forces. Nature uses supramolecular chemistry to form the double-helix of DNA or to fold proteins. For nanotechnology, single-layers of 2D structurally ordered materials – along the lines of graphene – could fill a great many needs but the key is to process them in solution.

“Solution-based processing allows for mass production and reduced manufacturing costs, and is an important step for transferring materials to a dry state without losing their structural integrity,” Yi says. “Solution-based processing also allows for bio-related applications such as biomimetic sensing, where the framework structure is advantageous for the capturing of guest molecules and the amplification of chemical signals.”

However, the self-assembly of well-defined 2D supramolecular systems polymers in solution has been a challenge because such polymers tend to precipitate out of solution, making them difficult to manipulate and characterize. To meet this challenge, Yi and his collaborators used a combination of self-assembling tripods and marocycle rings to form a porous framework with honeycomb periodicity, similar to that of a MOF, but which remains rigid in solution. Equipping the tripods with bulky hydrophilic groups that resist stacking preserved the solubility and single-layer 2D architecture of the framework.

“That our framework is held together by reversible, non-covalent supramolecular interactions ensures good solubility in water,” Li says. “The precise dimensional control of our solution-based processing facilitates the structural and chemical customization of our frameworks.”

The tripods of these SOFs were made from aromatic bipyridine molecules whose trio of struts or arms were interlocked with the struts of their neighboring molecules through the macrocycles, which were made from cucurbituril molecules. The molecules used in this study were proof-of-principle starters. Other molecules for the struts could be employed in the future for the design of similar or more complex architectures. The 2D single-layer structures of these first SOFs were characterized at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source, another DOE national user facility, using small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) technologies at beamlines 12.3.1 and 7.3.3.

Yi and his collaborators at the Molecular Foundry and in Shanghai are now working to create soluble SOFs in 3D.

Source: Berkeley Lab / Lynn Yarris