The most common cause of chronic low-back pain is the deterioration of discs between the vertebrae. However, how this happens is not completely understood. In a recent study, scientists claim to have uncovered a biological mechanism that not only slows this decline but also reverts it, providing a promising pathway for potential future treatments.

Chronic low-back pain arises from degradation of the tissue inside the disc or inflammation. To date, therapies to treat intervertebral disc degeneration are limited, involving broad-spec anti-inflammatory drugs, which have undesirable side effects, or surgeries that are invasive, risky, and require long recovery times.

“There is a clear need for alternative treatments prior to surgery that […] slow or reverse the progression of intervertebral disc degeneration,” said Jiangang Shi, professor in the Department of Orthopedic Surgery in Changzheng Hospital from Navy Medical University and co-lead author of the study published in Advanced Biology.

“The present study [could] broaden the horizon concerning how the [neuron activity] correlates with intervertebral disc degeneration and sheds new light on novel therapeutic alternatives,” he added.

A biological mechanism to combat low-back pain

When healthy, intervertebral discs play a crucial role in transmitting the weight placed on the spine and aiding in shock absorption. But when the discs start deteriorating, pain sets in, signaled by neurons in the area.

“We think that the [neurons’ influence] on intervertebral disc degeneration is not only limited to the occurrence of pain, but also intervertebral disc degeneration itself,” said Ximing Xu, professor in the Department of Orthopedic Surgery in Changzheng Hospital, and co-lead author of the study. “We believe that an enhanced understanding of […] the structural changes within intervertebral disc tissue and inflammatory responses will help identify novel therapeutic targets and enable effective treatment.”

Within the spine there are numerous chemical messengers released by neurons called neurotransmitters that carry signals and information between cells. In this study, the team chose to investigate the role of a neurotransmitter called vasoactive intestinal peptide, as it has previously been linked to anti-inflammatory effects, meaning it could have a protective effect on disc tissue.

Using tissue from donors, the team observed that cells in the nucleus pulposus, a jelly-like structure at the center of intervertebral discs, had a lower amount of this peptide receptor when degeneration increased. Moreover, when they inhibited the expression, they observed a reduction in the production of type II collagen and aggrecan, main components of nucleus pulposus tissue.

Challenges with peptide-based therapies for back pain

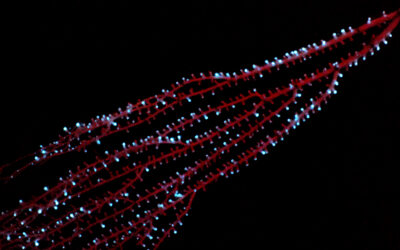

To probe whether this peptide might be used as a drug therapy to delay or prevent degeneration, the team treated mice with the peptide for four consecutive weeks. At various intervals, they took MRI images of the mice’s discs and used a technique for imaging proteins called immunofluorescent staining to observe progress. They found that in addition to slowing the progression of degeneration in the treatment group compared to controls, the peptide also improved levels of the protein aggrecan.

“This present study not only revealed the expression changes of vasoactive intestinal peptide [and its] receptors within human nucleus pulposus tissue, but also demonstrated [its] protective effects [against] degeneration,” said Jingchuan Sun, professor in the Department of Orthopedic Surgery in Changzheng Hospital, and co-lead author of the study.

Despite these promising results, the authors say they are a long way away from developing a drug for back pain based on this peptide, with one of many obstacles to overcome being formulation.

When taken orally, peptides are notoriously unstable and difficult to deliver to the target location, meaning it would be very unlikely that it would reach the nucleus pulposus directly. These types of therapies therefore generally require high doses and long treatment durations, which increase the risk of undesirable side effects. If applied locally via injection, as was done in the study, there is also a risk of structural damage as the needle could break the fragile external walls that protect the discs.

Sun thinks that a way to overcome these hurdles is to continue trying to understand more of the biological processes modulating the deterioration. He says the team plans to seek out more neurotransmitters, which might help bring them closer to identifying a viable therapy for those suffering from chronic back pain.

Reference: Kaiqiang Sun, Jiuyi Sun, Chen Yan, et. al., Sympathetic Neurotransmitter, VIP, Delays Intervertebral Disc Degeneration via FGF18/FGFR2-Mediated Activation of Akt Signaling Pathway, Advanced Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1002/adbi.20230025

Feature image credit: Kenny Eliason on Unsplash