Editing DNA—the genetic material we’re born with—to cure or model a rare disease may still sound like the stuff of science fiction but, for Alexis Komor, this is business as usual.

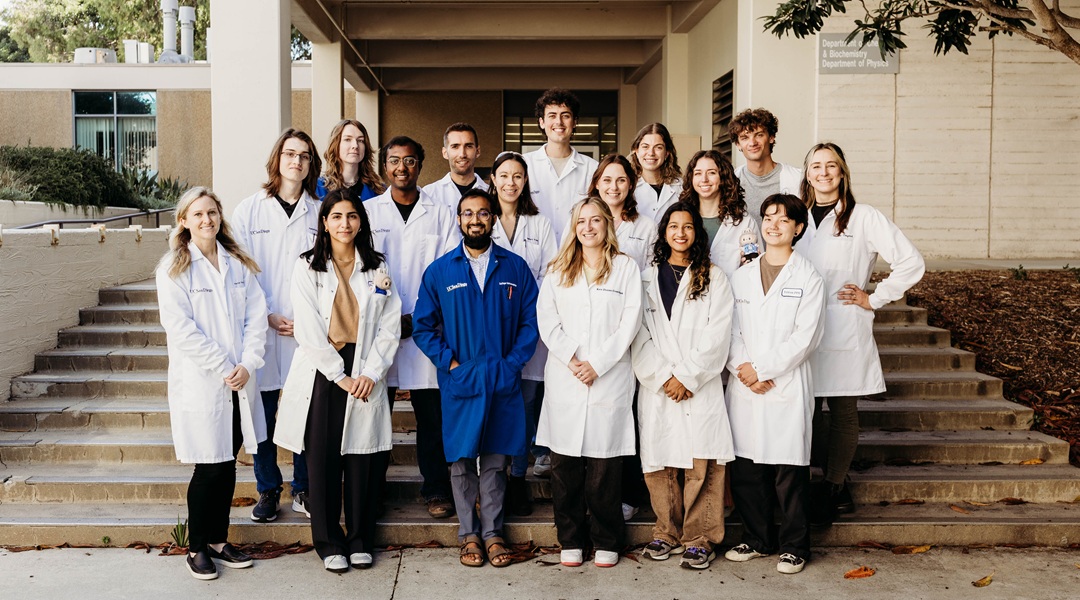

Komor, a professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of California, San Diego, and one of Advanced Science‘s 2025 Young Innovator Award winners, develops new tools to edit the human genome. While CRISPR-Cas9 acts like “molecular scissors,” allowing scientists to cut the genes that make up DNA, how cells repair that break in the DNA can’t be easily controlled—only a small percentage end up with the desired edit. During her postdoc, Komor developed an approach to help solve this efficiency problem. Her “base editing” technique acts more like a pencil and eraser, allowing a single DNA base to be precisely replaced. Now, Komor and her research group (pictured, with Komor bottom left) are focused on adding to the gene editing toolbox.

On your lab group’s website, you describe the overarching aim of your research as “functional investigation of human genetic variation and development of precision genome editing methodologies using chemical biology.” Could you unpack that?

For two people who are not related, their genomes will differ at millions of sites, which is called genetic variation. “Functional investigation of genetic variation” means figuring out what each of those variants or each of those differences is doing functionally for a person’s health and traits. Sometimes you have a single point mutation that, just on its own, definitively causes a disease or trait. Sickle cell disease is the most well known. However, there are other diseases, like cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, as well as most traits like eye color and hair color, where the combination of many differences throughout the genome results in the disease, trait, disease protection, etc.

It’s a very complicated problem, and it’s really hard to tease it apart and figure out what those particular combinations are. We really don’t understand human genetics well enough right now to know what those rules are. That’s what we’re trying to do [in my lab]: use genome editing to modify the sequences of the DNA of live cells in a dish, and then see how that alters the function of the cell using some sort of assay where we’re looking at something that’s related to the disease that we’re studying.

So, in this investigation of human genetic variation, you’re developing new genome editing methodologies in the process?

The way that we generate these models of human cells in a dish that have a particular mutation, or many mutations together—the way that we change the genome to have these variants in them—is through genome editing. We don’t have the full toolbox to be able to do whatever type of manipulation of the genome of the cells that we want. So, in the process, we’re trying to push forward the efficiency and the precision of the ways that we can manipulate the genomic sequence of these cells. Because the current toolbox is somewhat limited, this limits what we can do in terms of the cell models we can generate.

In what ways do the current gene editing tools fall short?

“Traditional genome editing,” as I call it, is your original CRISPR-Cas9 system. This is where to start the genome editing process you would use CRISPR-Cas9 to cut the DNA, like scissors. You cut the DNA in half, and then you try to manipulate the cell to repair it in a certain way where it puts, for example, an A-to-T mutation where you want it. Typically, the efficiency of this is quite low, so if you have a huge population of cells in which you’re trying to install this mutation, you’ll get that mutation in maybe 10% or less of the cells.

Because of the way in which DNA breaks and repairs, you can also get what we call genome editing byproducts, which is when the sequence has been changed in a way that we don’t want and can’t really control. Typically, with these double-stranded-break technologies, the cell will insert or delete random bases at the site that we cut, and those are called indels.

This can be helpful for certain applications, but if you’re trying to model a very specific mutation, then those indels are completely useless. They’re byproducts, essentially. So, these traditional double-stranded-break tools have major issues with efficiency and byproduct formation. That cut that we make with the scissors is also very toxic to the cell, so it can reduce the overall health of the cell, which can have bad implications for therapeutics.

When I was a postdoc, I developed this new technology called base editing. Instead of using scissors to cut the DNA, the analogy is a pencil and an eraser, where you can erase one base at a time, and then put in a new one by doing a chemical reaction on the actual DNA base. We can go to a specific location in the genome and do a chemical reaction to convert one base into another directly, without having to use the scissors or cut the DNA.

What’s the difference between base editing and prime editing?

With base editing, we do a chemical reaction on the actual DNA base. The efficiency is quite high, and we get much fewer byproducts, but you’re limited in the types of base-to-base transformations you can do, just because we only have two types of editors and limited chemical reactions we can perform on the genome. So, we can do C-to-T edits or A-to-G edits. Prime editing is another so-called non-traditional genome editing tool, where it rewrites sections of the genome. So, it will go in, cut one DNA strand, and then basically rewrite, for example, a 10-base-pair sequence into a new 10-base-pair sequence, making it much more versatile and ubiquitous. You can do whatever type of edit that you want. But the mechanism is also a lot more complicated, so overall efficiencies are still pretty low for prime editing, and it requires a lot of optimization. We work in the prime editing space as well, and we’re trying to improve those tools.

What are the main purposes of genome editing?

You can use it for so many things. Many non-scientists have heard about it because of its application in therapeutics. For example, people who have a genetic disease, you could cure that with a single treatment with a genome editor, going into their cells and correcting that mutation on the DNA level.

Could you explain how editing out a genetic disease would work? How would you perform that on somebody?

I can give you a specific example. A baby was born a little over a year ago with a defect in a really important gene that encodes for a protein that breaks down food. It’s called a urea cycle disorder. One of those proteins in that pathway had a mutation in it that was making it basically non-functional, so this baby couldn’t break down urea.

Basically, [doctors said] we need to fix this gene. It was a G-to-A mutation that made it nonfunctional. They needed to edit the A back to a G so that the gene would function normally. And because that gene is in every cell in our body, but it’s only expressed in—or important in—the liver cells, they said, okay, we could treat this baby and specifically, the cells in the baby’s liver. That should be enough for the baby to be able to process urea and be healthy. These base editors can be encoded in a big piece of mRNA, kind of like the COVID vaccine.

For the COVID vaccine, there’s a piece of mRNA that encodes a COVID protein, and when you give a patient the vaccine, the mRNA is delivered into cells in their immune system, and they express the protein that this mRNA encodes for. With the COVID vaccine, this is a protein that we need to make antibodies against.

For the genome editor, you have the mRNA that encodes for the base editor, or the genome editor in there, and then it’s packaged in a lipid nanoparticle. It’s very similar to the COVID vaccine, just a slightly different chemical formulation of the lipid nanoparticle, so when they injected it into the baby, it delivered the mRNA into the liver cells. Then, the mRNA is translated into the base editor—or the genome editor protein—and then it can go into the nucleus, into the genome, and correct that A back into a G.

It’s really tricky for genome editors to be employed as therapeutics. It’s not just work that needs to be done on the genome editing side; tons of work also needs to be done on the delivery side, where we can deliver that genome editor specifically to whichever cells it needs to go to. We don’t work on the delivery side, but we have a lot of collaborations, especially with other labs on campus who’ve been studying a disease for a really long time and say “this would a great disease to develop a genome editing strategy against.”

They have all the disease biology expertise, and we can optimize a genome editing strategy to correct that disease. We usually need some kind of delivery expert to make it happen, and we can work with some of the local biotech companies. There are a lot that focus on new types of delivery mechanisms.

Another major goal in your lab is to solve the variant interpretation problem. What is it?

Take a person’s genomic sequence. You can see, okay, here are all these variants, or these mutations, where their genomic sequence is different from someone else’s or the reference genome.

How do we interpret that? What are those mutations doing in terms of health or traits?

When it’s a monogenic disorder or monogenic mutation like sickle cell disease, that mutation alone causes a very distinctive phenotype. Those are much more straightforward to interpret and figure out what those mutations are doing. But combinations of hundreds or thousands of variants that together cause a trait or a disease? It’s really hard to figure that out.

So, variant interpretation is looking at a person’s sequence, what variants or mutations they have, and then interpreting how that’s going to impact their health or traits.

How can it be solved?

There’s lots of computational work being done. In genome-wide association studies, where you sequence many people — a control population of healthy people and your sample population who are all suffering from the same disease. Then, you try to figure out what mutations are in one population but not the other, or whatever combinations of variants. That’s what the field has mostly done in the past.

I think the issue is that a lot of these mutations are very rare, so it’s hard to see them in many individuals, and so it’s hard to get statistical power. But if we can reverse engineer them in our cell lines in the lab and have a robust readout, we could know what they’re doing. For example, we’re interested in cancer. It’s generally known that there are mutations in a certain gene or region of the genome where people who have them get this type of cancer.

We can develop some kind of assay to tell if we’ve given cells cancer or not, which is usually whether they start growing rapidly out of control. And then we introduce mutations or combinations of variants into the cells, and then run this assay to figure out if we gave the cell cancer when we installed these mutations. We think the best way to do this is to scale it up in high throughput so you can look at thousands of mutations or combinations of mutations in a single experiment.

Have you been able to do high-throughput gene editing in your lab?

We have a couple projects that we call high-throughput base editing or genome editing. But it’s hard to set up the assay, and then it’s hard to get the genome editing to occur with high enough efficiency, for hundreds or thousands of variants in a single experiment. It’s technically difficult.

With variant interpretation, is the goal to be able to predict whether or not somebody will develop a disease, or to treat it? Or both?

One gene that we’ve been looking at is called MUTYH. We published a research paper about it this past year. Some mutations [in this gene] can cause colorectal cancer, but many variants have been identified in people, and whether they’re cancer-causing or benign is uncertain. So, we generated cell lines where we’ve installed these variants.

And then we say, okay, this one messes up the function of the protein, so it probably would cause cancer. If a person did a whole genome sequencing and found that they had the mutation, then you could think about correcting it in their digestive system. Or you can go through diagnostic testing. You could start getting colonoscopies earlier, because if you can detect a cancerous polyp early on, then you can just remove it, and the odds of survival are greatly improved.

So, those are the two strategies: “This is really bad, we need to correct it” or “We’re aware that this person is at increased risk, so we should monitor them.”

You’re involved in some outreach at UC San Diego. Can you tell me about your outreach activities?

We developed a three-day mini course on genome editing and bring it to local high schools. We reach out to the teachers and usually do it with a biology class, juniors or sophomores, so they have a little bit of background in molecular biology. Then, we basically take over their class for three days, me and three or four grad students from the lab. We do an introductory lesson on what genome editing is and what it can be used for, and on day 2, the students do a lab experiment. We bring them E. coli, these bacterial cells that have a genetic disease, and then they design a base editor to deliver into the bacterial cells.

They can see it correct this genetic disease because it makes the bacteria glow green when it’s been corrected. On day 3, they visualize their bacteria to see if they were able to correct the mutation, and we talk about the ethics of genome editing and do a panel discussion about careers in science and research.

What academic achievement are you most proud of?

I’m most proud of my lab alumni. I’ve graduated eight grad students from my group with their PhDs, so I’m very proud of that. Big publications out of the lab are exciting, but when my students schedule their thesis defense, and have their hour-long seminar presentation in front of people, and I get to introduce them and shake their hand and congratulate them. I think that’s the highlight of my career.