A new class of tiny, injectable LEDs is illuminating the deep mysteries of the brain.

Researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Washington University in St. Louis have developed ultrathin, flexible optoelectronic devices – including LEDs the size of individual neurons – that are lighting the way for neuroscientists in the field of optogenetics and beyond.

Led by John A. Rogers, the Swanlund professor of materials science and engineering at the U. of I., and Michael R. Bruchas, a professor of anesthesiology at Washington University, the researchers published their work in the April 12 issue of the journal Science.

“These materials and device structures open up new ways to integrate semiconductor components directly into the brain,” said Rogers, who directs the Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory at the U. of I. “More generally, the ideas establish a paradigm for delivering sophisticated forms of electronics into the body: ultra-miniaturized devices that are injected into and provide direct interaction with the depths of the tissue.”

The researchers demonstrated the first application of their devices in optogenetics, a new area of neuroscience that uses light to stimulate targeted neural pathways in the brain. The procedure involves genetically programming specific neurons to respond to light. Optogenetics allows researchers to study precise brain functions in isolation in ways that are impossible with electrical stimulation, which affects neurons throughout a broad area, or with drugs, which saturate the whole brain.

Optogenetics experiments with mice illustrate the ability to train complex behaviors without physical reward, and to alleviate certain anxiety responses. Yet fundamental insights into the structure and function of the brain that emerge from such studies could have implications for treatment of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, depression, anxiety and other neurological disorders.

While a number of important neural pathways now can be studied by optogenetics, researchers continue to struggle with the engineering challenge of delivering light to precise regions deep within the brain. The most widely used methods tether the animals to lasers with fiber-optic cables embedded in the skull and brain – an invasive procedure that also limits movements, affects natural behaviors and prevents study of social interactions.

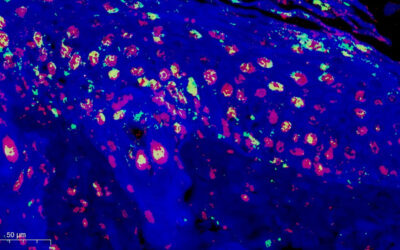

The newly developed technologies bypass these limitations with specially designed powerful LEDs – among the world’s smallest, with sizes comparable to single cells – that are injected into the brain to provide direct illumination and precise control. The devices are printed onto the tip end of a thin, flexible plastic ribbon – thinner than a human hair and narrower than the eye of a needle – that can insert deep into the brain with very little stress to tissue.

“One of the big issues with implanting something into the brain is the potential damage it can cause,” Bruchas said. “These devices are specifically designed to minimize those problems, and they are much more effective than traditional approaches.”

The active devices include not only LEDs but also various sensors and electrodes that are delivered into the brain with a thin, releasable micro-injection needle. The ribbon connects the devices to a wireless antenna and a rectifier circuit that harvests radio frequency energy to power the devices. This module mounts on top of the head and can be unplugged from the ribbon when not in use.

“Study of complex behaviors, social interactions and natural responses demands technologies that impose minimal constraints,” Rogers said. “The systems we have developed allow the animals to move freely and to interact with one another in a natural way, but at the same time provide full, precise control over the delivery of light into the depth of the brain.”

The complete device platform includes LEDs, temperature and light sensors, microscale heaters and electrodes that can both stimulate and record electrical activity. These components enable many other important functions – for example, researchers can measure the electrical activity that results from light stimulation, giving additional insight into complex neural circuits and interactions within the brain.

The breadth of device options suggests that this wireless, injectable platform could be used for other types of neuroscience studies – or even applied to other organs. For example, Rogers’ team has developed related devices for stimulating peripheral nerves in the leg as a potential route to pain management. They also have built devices with LEDs of multiple colors, so that several neural circuits can be studied with a single injected system.

“These cellular-scale, injectable devices represent frontier technologies with potentially broad implications,” Rogers said. His group is known for its success in the development of soft sheets of sophisticated electronics that wrap the brain or the heart or that adhere directly to the skin.

“But none of those devices penetrates into the depth of tissue,” Rogers said. “That’s the challenge that we’re trying to address with this new approach. Many cases, ranging from fundamental studies to clinical interventions, demand access directly into the depth. This is just the first of many examples of injectable semiconductor microdevices that will follow.”