Material scientists at ETH Zurich and the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces in Potsdam have developed a new type of sensor to measure CO2. Compared with existing sensors, it is much smaller, has a simpler construction, requires considerably less energy and has an entirely different functional principle.

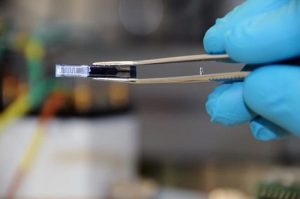

The new sensor consists of a recently developed composite material that interacts with CO2 molecules and changes its conductivity depending on the concentration of CO2 in the environment. ETH scientists have created a sensor chip with this material that enables them to determine CO2 concentration with a simple measurement of electrical resistance.

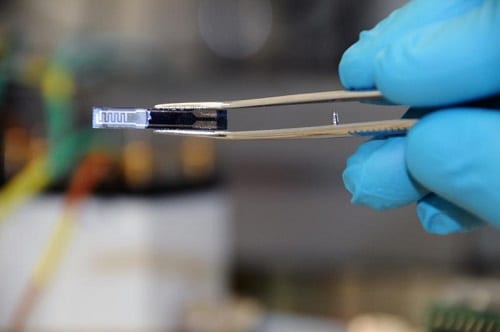

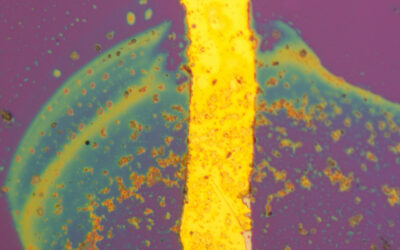

ETH researchers’ miniature CO2 sensor: chip with a thin layer of the polymer-nanoparticle composite. (Photo: Fabio Bergamin / ETH Zurich)

The basis of the composite material is a polymer made up of salts called ionic liquids, which are liquid and conductive at room temperature. The name of the polymers is slightly misleading as they are called poly ionic liquids (PIL), although they are solid rather than liquid.

Scientists worldwide are currently investigating these PIL for use in different applications, such as batteries and CO2 storage. From their work it is known that PIL can adsorb CO2. “We asked ourselves if we could exploit this property to obtain information on the concentration of CO2 in the air and thereby develop a new type of gas sensor,” says Christoph Willa, doctoral student at the Laboratory for Multifunctional Materials.

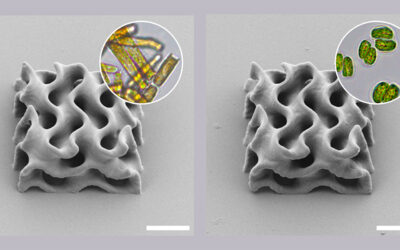

Willa and Dorota Koziej, a team leader in the laboratory, eventually succeeded by mixing the polymers with specific inorganic nanoparticles that also interact with CO2. By experimenting with these materials, the scientists were able to produce the composite. “Separately, neither the polymer nor the nanoparticles conduct electricity,” says Willa. “But when we combined them in a certain ratio, their conductivity increased rapidly.”

The scientists were surprised that the conductivity of the composite material at room temperature is CO2-dependent. “Until now, chemoresistive materials have displayed these properties only at a temperature of several hundred degrees Celsius,” explains Koziej. Thus, existing CO2 sensors made from chemoresistive materials had to be heated to a high operating temperature. With the new composite material, this is not necessary, which facilitates its application significantly.

Existing devices that can detect CO2 measure the optical signal and capitalise on the fact that CO2 absorbs infrared light. In comparison, researchers believe that with the new material much smaller, portable devices can be developed that will require less energy. According to Koziej, “portable devices to measure breathing air for scuba diving, extreme altitude mountaineering or medical applications are now conceivable”.