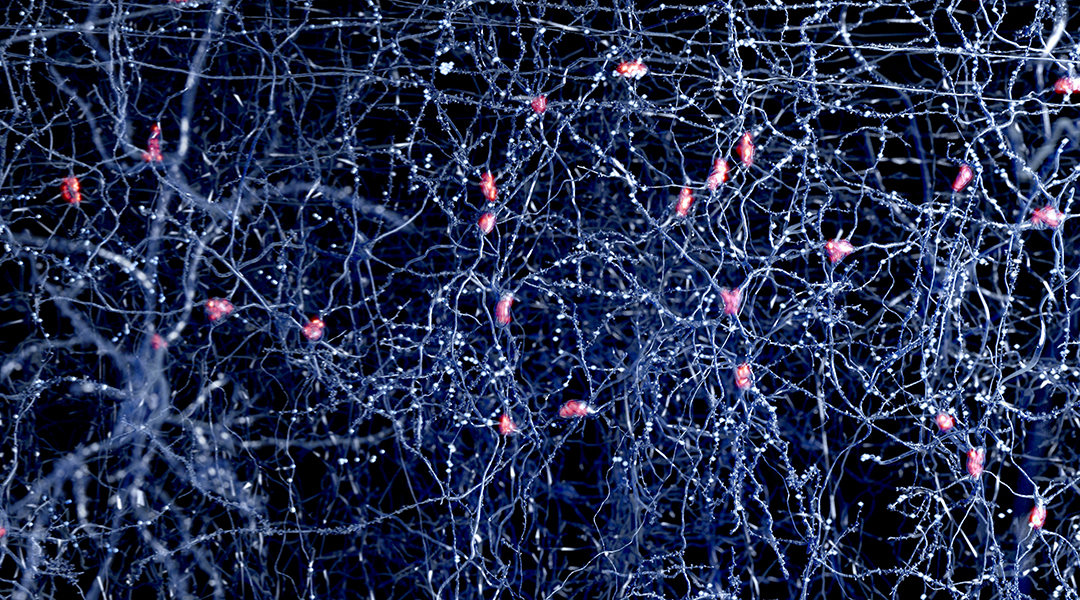

Throughout our lives, significant events are saved by the brain’s neurons and stored as memories. But memories don’t sit alone. Normally, they are connected to a number of others, making a reasonable reconstruction of events in a rational timeline.

“Real-world memories are formed in a particular context and are often not acquired or recalled in isolation,” wrote a group of scientists led by Alcino Silva from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). “Time is a key variable in the organization of memories, as events that are experienced close in time are more likely to be meaningfully associated, whereas those that are experienced with a longer interval are not.”

The team is interested in exploring mechanisms involved in memory formation to better understand the process of linking memories — how one memory can trigger the recall of another in a sequential series of events that took place within a certain period of time.

In a recent study, the UCLA team reported that the activation of a protein called CCR5 acts as a biological switch that defines the size of the time window that connects subsequent memories together — manipulating it could lead to better memory loss treatment.

This was intriguing to the team as CCR5 is a protein found in immune cells and has been studied extensively as a result of the role it plays in the inflammatory response during HIV infections, as the virus uses it to enter human cells. “Discovering the involvement of CCR5 in memory was a surprise,” said Silva, professor of neurobiology and psychology at the UCLA. “Years ago, our research team was looking for ‘new’ proteins involved in memory, and to our amazement, we found that CCR5 was one of them.”

In mouse models, they found that CCR5 activation in neurons of the hippocampus — a brain region involved in memory formation — stops connecting memories to one another in mice subjected to behavioral models of memory.

The mice were exposed to two different events separated by an increasing period of time. The scientists observed that if CCR5 activation occurred in between both events, mice weren’t able to relate one event to the other, but when both events occured before CCR5 activation, the mice related the memory of the first event to the second.

The precise coordination of memory systems in the human brain is very important, as when dysfunction in memory linking occurs it can lead to problems which manifest in diseases such as dementia, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer’s disease.

“There are so many causes for memory loss affecting the lives of millions of people and there’s so little that we can do for them,” said Silva. “Memory dysfunction can appear in cases of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and even in patients undergoing cancer treatment.”

Gradual memory loss also occurs naturally during aging — an event that also occurs in mice. As a result, the team used a middle-aged mouse model to study how CCR5 manipulation could help improve memory loss treatment in this scenario.

The solution presented itself in the form of a drug named maravidoc, which blocks the activity of CCR5 and has been used to treat HIV infection where the molecule binds CCR5 proteins, interfering with virus’ ability to enter cells.

After treating middle-aged mice with the drug, they observed that the size of the time window in which mice could link memories together was extended, and their memory recovered similar features to those seen in younger mice.

“When we used maraviroc, we were able to reverse the memory deficits in middle-aged mice,” said Silva. This discovery suggests that maravidoc could be a potential memory loss treatment to help people suffering from memory dysfunction.

Repurposing maravidoc could be straight forward as it is already in clinical use and has been proven to be safe over long periods of time in patients with HIV. Importantly, different studies have shown that maravidoc reaches the brain when given systemically, providing an opportunity to target CCR5 in neurons without the need for invasive procedures.

“There’s a great need for memory drugs,” said Silva. “The few memory drugs that are being used in the clinic help patients, but with a very little effect. The wonderful thing about this study is that we already know that maravidoc is relatively safe and it’s very likely that people suffering from memory deficits may be able to use it for extended periods of time.”

Reference: Yang Shen, et al, CCR5 closes the temporal window for memory linking, Nature (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04783-1

Feature image credit: Shutterstock/Juan Gaertner