Illustration: Kieran O’Brien

This week marked the 138th birthday of Scottish microbiologist, pharmacologist, and physician, Sir Alexander Fleming. He is best known for discovering the world’s first antibiotic in 1928—benzylpenicillin—from the mould Penicillium notatum, purely by accident, but an accident that would revolutionize healthcare.

The story of science is often the story of chance discoveries and complete accidents. Think Isaac Newton sat under his apple tree (allegedly), and coming up with his theories on gravity; or Wilhelm Röntgen toying with cathode ray tubes when a fluorescent screen nearby was seen to be glowing, despite the tube being covered with cardboard, leading to his naming of some as-then-unknown “X” ray that was penetrating the opaque cardboard.

Alexander Fleming’s story was no different, or indeed might not have happened at all, as a career in science wasn’t always the obvious choice for him.

Born in 1881, Fleming was the third of four children, raised on a farm in the lush countryside of Ayrshire in south-west Scotland. His first steps into science was when his brother, Tom, suggested he take up medicine, and so Alexander enrolled at St Mary’s Hospital Medical School. However, whilst medicine was his field of study, he had also been pursuing a military career since 1900, and eventually served as a captain throughout the First World War in the Royal Army Medical Corps.

It was during his time on the Western Front that he first became interested in studying antibacterial substances, as he saw first-hand that sepsis was a major killer for soldiers in the battlefield. At the time, antiseptics were the only line of defense against wound infection, but these were unreliable and sometimes even made infections worse. Having survived the war—a fortune which could well have set-back the discovery of antibiotics for years had things turned out differently for him—he returned to St Mary’s where he would establish himself in the medical field as a brilliant researcher, even before his ground-breaking discovery in the next decade.

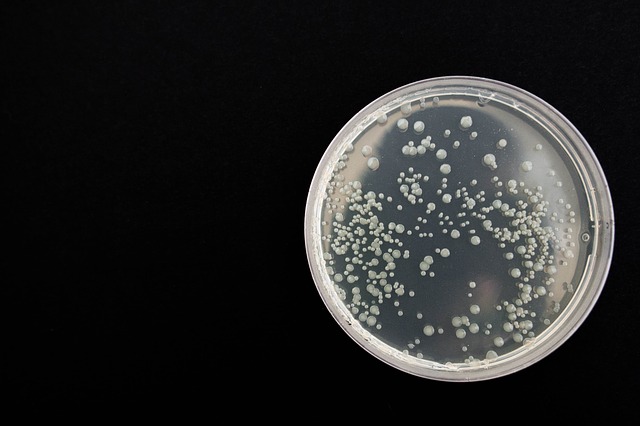

Despite his respected reputation, it is perhaps his “sloppiness” that is largely thankful for his discovery of benzylpenicillin; it was only due to his notoriously messy and unkempt laboratory that caused one of his cultures of staphylococci—which he was studying at the time—to be contaminated with mould spores, which, when he returned to lab some weeks later after a family holiday, had appeared to inhibit the growth of the bacteria culture around this mould. It didn’t take long for Fleming to isolate the compound that caused this “funny” effect, as he modestly put it. Thus, with this isolated compound—benzylpenicillin—the world’s first antibiotic was born.

Initially, Fleming was skeptical that this would be an effective treatment for bacterial infections, primarily because in the first years following 1928, penicillin was difficult to produce en mass. It wasn’t until the US and British governments poured money into researching how to produce this on a large scale, owing to the outbreak of another world war, that penicillin became a practical tool against infection; by D-Day in 1944, penicillin was being widely used to treat injured soldiers of the Allied forces.

Despite winning the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1945 for this achievement, he nevertheless still stressed the accidental aspect of this discovery, modestly saying, “One sometimes finds, what one is not looking for. When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.”

Thanks to Alexander Fleming, who died in 1955, the rest of the twentieth century saw medicine make huge leaps forward; survival rates from surgery soared, as what was risky in earlier times wasn’t so much the surgical procedure itself, but the susceptibility to infection afterwards, which could often prove fatal; organ transplants which before were impossible, became standard procedures for many patients; and many other bacterial infections and diseases which would normally be fatal, became as treatable as the common cold.

But on a cautionary note, Fleming was rather prescient about the current challenges in this century with regards to “superbugs” and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. He himself recognized early on that bacteria could evolve such resistance, and it was therefore important to use antibiotics appropriately and only as a last line of defense.

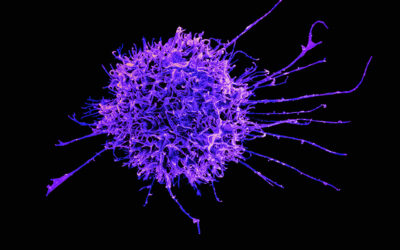

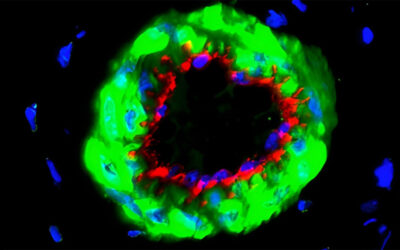

As we have become more aware in recent years that antibiotics are no longer the wonder-cure they once were, the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is spurring the current medical community to come up with new ways to treat infection with modern techniques. In some cases, old techniques used before antibiotics are being rejuvenated with modern upgrades, such as photodynamic antibacterial therapy, which is once more a growing field of research.

The history of science is often made by standing on the shoulders of giants, and so whilst antibiotics may prove to be a treatment of the past in the coming decades, the discoverer of these—Alexander Fleming—need not be a footnote in the history of science, but a pioneer who revolutionized science in one century, and whose legacy could be built on in the next.

To read about other pioneers in science, you can access our Pioneers series here.