From creating a manufacturing process for making plastics using supercritical carbon dioxide to his latest biomedical venture, Liquidia Technologies, professor Joseph DeSimone of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University has a long and distinguished career as an entrepreneur, as well as a scientist.

From creating a manufacturing process for making plastics using supercritical carbon dioxide to his latest biomedical venture, Liquidia Technologies, professor Joseph DeSimone of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University has a long and distinguished career as an entrepreneur, as well as a scientist.

But what gives an entrepreneur the tools to succeed? We talk to Prof. DeSimone about the value of a liberal arts education in shaping future startup creators, as well as about what he has been recently up to with Liquidia Technologies.

Can you give me a brief pitch about your latest venture and what is its purpose?

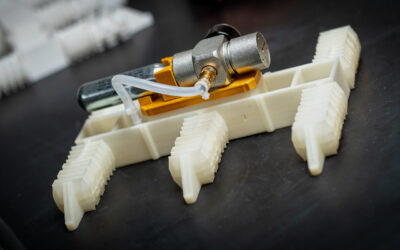

My latest venture, Liquidia Technologies (Research Triangle Park, North Carolina), is developing new vaccines and medicines with the PRINT (Particle Replication In Nonwetting Templates) technology invented in my academic laboratory at the University of North Carolina (UNC). PRINT is a nanoparticle fabrication technique that fuses precision manufacturing processes found in the microelectronics industry with the continuous roll-to-roll web based processes from the photographic film industry, PRINT enables mass production of particles with tailored shapes, sizes, flexibility, and chemical composition. The technology was licensed to Liquidia from the University, and Liquidia has successfully refined it and scaled it up. The company currently has its first product—a seasonal PRINT nanoparticle-based influenza vaccine—in clinical trials.

What is your role within the company, and how much are you involved now with the business side of the company?

I remain very active with the company and formally serve on the Board of Directors. Further, my academic lab at UNC and Liquidia have a strong working partnership.

Recently, the Governor of North Carolina was the latest American lawmaker to criticize liberal arts degrees and State funding for such programs. You graduated from a liberal arts college, and recently in an extended Twitter exchange you described the liberal arts background as fundamental for an entrepreneur, can you elaborate?

You can never overestimate the impact your education has on the way you view the world. Certainly, I would not be where I am today were it not for my educational experiences. My undergraduate liberal arts education at Ursinus College shaped my approach to scientific research and entrepreneurship. Most importantly, it has shaped me as a person. As an entrepreneur specifically, it is crucial to be able to understand and make judgments in context—to see the big picture and make connections among concepts, among seemingly disparate fields of study, and among people with different perspectives, personalities, and areas of expertise.

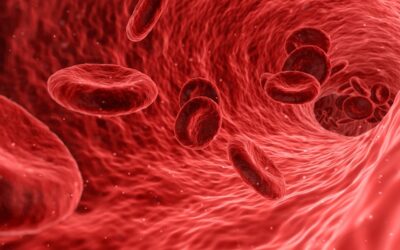

Part of this involves being able to think across traditional boundaries to identify unique opportunities for innovation. PRINT, for example, merges concepts and processes from the computer industry and the photographic film industry; it is enabled by our expertise in chemistry and also by the representation of other fields in our group (e.g. immunology; pharmacology). PRINT has diverse applications in nanomedicine including better diagnostics and targeted treatments for cancer, progress toward development of synthetic blood, and the creation of better and cheaper vaccines. But PRINT wouldn’t have happened without the insight of a talented group of scientists, my team of students and staff, who bring diverse perspectives and ways of approaching problems to the table. Only through meaningful discourse in our group do we make our greatest advancements. And we have a very diverse group—of discipline, culture, background, problem solving styles.

Our success as a group rests on cooperation, dialogue, mutual respect, and the willingness to work hard and challenge the status quo to solve problems. It also involves necessary disagreement, asking tough questions, having difficult conversations, and learning from failure. Insight to enable the kind of creative thinking and problem solving that resulted in PRINT doesn’t happen by accident; the insight to be able to achieve such a technology isn’t lucky.

My liberal arts education showed me the value in carefully thinking about concepts from different disciplines, and also in bringing people together who have diverse backgrounds around a common problem. It fundamentally shaped my approach as a researcher, professor, mentor, and entrepreneur.

A liberal arts education was preparation for this. It enabled—and enables—me to be adaptable. It showed me the importance of effective communication for any situation—in science, in business, in life. It also showed me the purpose of respect for different perspectives and different cultures. A liberal arts education enables cultural understanding. Our global economy is a rapidly changing one, fueled by the fast advances in technology. It is important to be able to understand cultural differences in order to exercise good judgment in the global business arena. Overall, my training in chemistry has allowed me to have success as a chemist in the laboratory, but my liberal arts education is what has allowed me to be innovative and have success in my career, in science, education, and business.

There is a difference between education and training. UNC is a public university system founded with a very specific purpose: to educate. Currently, we need to educate our students to be able to adapt to jobs that haven’t been created yet, to use technologies that haven’t been invented yet. That’s the fact of the matter. Technology is moving rapidly enough to change the nature of the workforce at a significant pace. This is in some ways evidenced by the fact that people are changing jobs a lot more frequently than ever before—something like 10 jobs on average before the age of 35 or 40. To be good at being adaptable, one must be able to think critically in many different types of situations. A liberal arts education fosters this. This constant change necessitates adaptability. If we are going to be competitive as a region economically, and as a state, we need to be sure we’re leveraging the resources we have through the UNC system, through Research Triangle Park, and elsewhere. There are strong resources in North Carolina that train students for specific jobs upon graduation. We also have to make sure we are preparing future leaders who are highly skilled in being adaptable. A liberal arts education—and the availability of it to everyone—is necessary for this.

Change is going to be constant in our 21st century economy, and liberal arts education prepares students best for this dynamic situation. It is key to have the ability to be a life-long learner, to be adaptable in practice, and to successfully engage in critical analysis in new environments all the time (and adjust on the fly). These are just some of the ways that a liberal arts education positions the best and brightest in our state to success in business and in our economy.

How influential was the environment you were in, at the University of North Carolina, for your entrepreneurial activity?

At the beginning of my career my mentors at UNC played an especially strong role in encouraging me to pursue opportunities to commercialize discoveries that my students and I made in the lab. UNC has a culture that values entrepreneurship, and this culture has strengthened significantly over time, especially in recent years. This plays a strong role in enabling ventures based on innovations made in the academic setting to move forward. UNC now has an impressive number of initiatives and policies to cultivate university-based entrepreneurship. Something that I had the opportunity to work on recently was the development of the Carolina Express License Agreement, which simplifies and expedites the licensing process by which new startup companies are spawned from University-based innovations.

When did you figure out that there was a good opportunity for commercial exploitation of the PRINT technology?

Almost right away it was clear that PRINT had the potential to change the way scientists approach the development of novel particulate vaccines and therapeutics. PRINT enables precise control over particle parameters like chemical composition, size, shape, deformability, and surface chemistry. This level of control in the fabrication of particles using biologically relevant materials was unprecedented. With PRINT, new opportunities were opened to examine the effects of particle size and shape on fundamental biological processes, such as how cells internalize particles and how particles are circulated throughout the body. PRINT also enables the mass production of particles that are highly uniform, which is a unique capability for the manufacture of biologically relevant nanoparticles. One of the most exciting things is that the scalability of PRINT creates the potential to drive down the cost of vaccines. Cheaper vaccines are desperately needed in the developing world.

How long was the process from the “idea” to the creation of the company?

It took only a few months. With a strong sense that we were doing something that was unprecedented, and with prior entrepreneurial experience, the process to set up the company happened fairly methodically. It helped that this was not my first venture; I had gotten my feet wet as an entrepreneur very early in my career through the commercialization of a new, environmentally friendly process to manufacture high-performance plastics, and then also a new, more environmentally friendly dry cleaning process.

Before starting your first venture, did you want to become an entrepreneur?

I was always interested in tackling problems. But I first did this in areas that were relevant to big companies, like DuPont. They had interest, for example, in the use of supercritical carbon dioxide as a solvent for polymerization of tetrafluoroethylene to make Teflon. With experiences, and at the urging of students in my group, I ventured out to launch a company of our own.

What is the main change in mindset that all these ventures brought to you? What is the most important thing you could not have possibly understood had you not participated in the founding of companies?

I think starting companies makes our science better. Let me explain. As we all know, when we publish papers, the peer review process makes our papers better. The critiques we get are “gifts”: although it doesn’t always feel like that at the time, they are. When one starts companies, it is like peer review on steroids! Top-notch people, even Nobel laureates, are brought in to evaluate our science. It makes us better!

What advice would you give to someone with a good idea who wants to commercialize it?

Get a good lawyer first! And go see the technology transfer office and go speak with the most experienced entrepreneur they can get to for advice.

How has this changed your interaction with other scientists?

I get a chance to speak with a wider range of folks than I would have been exposed to had I not been entrepreneurially active.

How important do you think being an entrepreneur is in today’s academic world? Do you think departments are more likely to “like” a candidate if s/he has an entrepreneurial background?

I think having an entrepreneurial background is becoming more and more common for candidates, and also more and more embraced.

How do you juggle your time between your academic career and your companies?

Carefully. It takes a lot of coordination and time management. It’s not easy, but it is rewarding and satisfying. It’s worth the extra effort!