Researchers led by Professor George Whitesides at Harvard University have developed inexpensive robots that can stretch, bend, and twist under control, and lift objects up to 120 times their own weight. Being soft, they can apply gentle and even pressure, and adapt to varied surfaces.

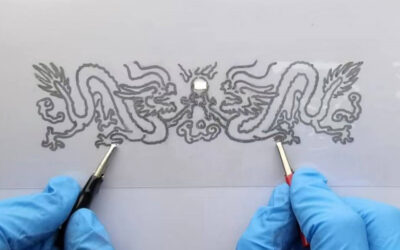

The fact that paper can bend but not stretch is the key to this remarkable invention. The team of researchers have encased a paper sheet in an air-tight elastic material derived from silicones, sometimes called silicon rubbers. On one side of the paper, the silicone is laced with tiny air channels. As air is pumped into the channels (termed PneuNets), the rubbery material on that side expands, forcing the paper to bend. Postdoctoral researcher Ramses Martinez likens the structures to balloons, “When the balloon part of the structure expands it doesn’t become round (as does a child’s balloon), but adopts more complex shapes in response to the constraints imposed by the paper sheets.”

Indeed, quite complicated shapes and movements can be created by simply altering the pattern of channels and by folding the paper in a process the researchers liken to origami. “The methods we developed are astonishingly simple for the complex motions that they generate. Once we understood the materials to use, the best procedures for fabrication and the kinds of designs that worked best.”

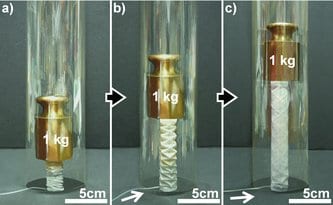

Actuators are what scientists call devices that move or change shape in response to some input and are the moving parts of robots. In their recent Adv. Funct. Mater. paper, the researchers given examples of contracting actuators (an example of which is shown in the video below), elongating actuators, and pleated bellows.

One bellows only 8.2 grams itself is shown to lift a 1 kilogram weight. Restricting movement further by gluing folds or fastening them together with paper strips can cause the shapes to turn corners or twist as they expand. The scientists drew inspiration from the motions of starfish, worms and squid, but used pneumatics and compressed air rather than muscles.

Production is simple: a mold is used to create pneumatic channels in the elastomer, which is then bonded to elastomer-soaked paper. Compressed air is pumped into the channels through a small valve. Alternatively, for bellows-type operation, a pleated cylinder of paper is soaked in elastomer, the cylinder is capped, and air is pumped into the centre of the cylinder. A strip of elastomer linking the caps ensures the paper returns fully to its original shape and size on the removal of air.

The work combines Prof. Whitesides’ previous experience of “squishy” robots using silicon-based materials and pneumatic activation with his development of paper as a support for tiny, low-cost, ‘microfluidic’ analytical devices.

Dr. Martinez is enthusiastic about the future for the paper robots, “We hope these structures can be developed into assistants for humans. Unlike the types of (machines) robots used in assembly lines (which are designed to be very strong and fast, but they are also very dangerous for humans to be around when they are operating), these actuators can be more ‘human-friendly’. They might, thus, provide ‘extra fingers or hands’ for surgeons, or handle easily damaged structures, such as eggs or fruit.” Use in disaster relief, where ability for machines to navigate complex pathways would be advantageous, is also envisaged. By adding such things as light sources, or metal wires to allow electrical conductivity, potential applications are considerably broadened.