A molecule is able to walk back and forth upon a five-foothold pentaethylenimine track without external intervention.

Within each of the cells in our bodies, and between individual cells, there are permanent transport processes occurring over distances ranging from a few nanometers to several millimeters. One of these cellular “cargo carriers” works by means of molecular motors that “walk” along the filaments of the cellular skeleton (cytoskeleton). British researchers have used these as inspiration to develop a molecular “track”, along which a small molecule can move back and forth like a courier. Their system is described in the journal Angewandte Chemie.

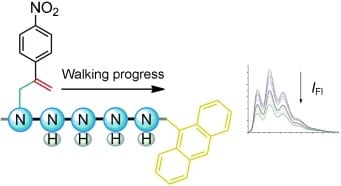

David A. Leigh and a team at the University of Edinburgh (UK) made their track from an oligoethylenimine. The filament contains amino groups that act as “stepping-stones” for the molecular “walker”. The walker is a small molecule (α-methylene-4-nitrostyrene). It resembles a stick figure that has an aromatic six-membered ring of carbon atoms for its torso, a nitro group for its head, and two short hydrocarbon legs. The molecule is initially bound to the first stepping-stone of the track by one leg. The molecular walker’s movement begins with a ring-closing rearrangement (an intramolecular Michael reaction). This causes the second leg to bind to the neighboring stepping-stone. A second, ring-opening rearrangement reaction (a retro-Michael reaction) then causes the first leg to detach from its stepping-stone. This allows the molecular walker to move along the track step by step.

There is, however, a catch: All of these rearrangement reactions are equilibrium reactions. If the stepping-stones are chemically equivalent, the tiny walker swings back and forth, lifts one leg and puts it down again, moves forward one step then back again; its movement has no directionality. However, it manages on average an amazingly high 530 “steps” before completely coming off the track. That is significantly more than natural systems like the kinesin motor proteins.

The miniature walker can even carry out a task: The researchers attached an anthracene group to the end of a track with five stepping-stones. As long as the walker stays at the beginning of the track, the anthracene fluoresces. However, if the walker reaches the anthracene end of the track, an electronic interaction between the walker and the anthracene “switches off” the fluorescence. The researchers found that the intensity of the fluorescence slowly sinks by about half. The final intensity is reached after about 6.5 hours, at which point there is an equilibrium between all possible positions of the walker.

The team’s next goal is to develop a walker that uses a “fuel” to march in a predetermined direction to transport cargoes over longer, branched tracks.