The 2014 discovery of a female “penis” in a species of Brazilian bark lice provoked understandable controversy, and led to the awarding of an Ig Nobel Prize to the researchers in question. Three years later they followed up this work by reporting that an African genus in the same tribe had independently evolved similar organs.

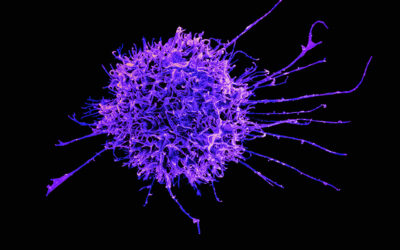

The bugs in question.

This second discovery begs the question: What are the evolutionary factors that might lead to such an apparent role reversal? The international research team have laid out their initial hypotheses in a fascinating essay recently featured in Bioessays.

The selective pressures that lead to the development of male penises and female vaginas are generally accepted. In species where females have a lower optimal rate of re-mating compared to their male counterparts, there is considerable selection pressure on the males to develop “persistence” in their genitalia. For example, spikes for clinging to unwilling mates. In females, there is a corresponding selection pressure on developing “tolerance” in their genitalia. For example, thickened walls or membranous pouches.

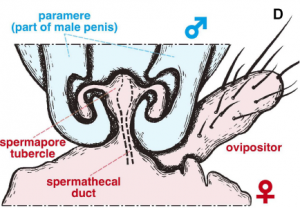

While this type of arrangement might seem to be the standard from a homo sapien standpoint, nature has no such bias. Most bird species reproduce through close contact of the terminal opening of their digestive system – the cloaca. Many insect species reproduce via the touching of a flat “spermapore” plate in the female with a membranous opening in the male.

Given the plurality of different genital shapes used by the animal kingdom, it is perhaps unusual that a female “penis” had not been observed before 2014. Research on these species is still in its early stages, but initial anatomical studies give a starting point for understanding the selection pressure that might lead to such a situation.

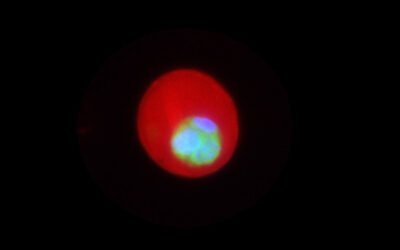

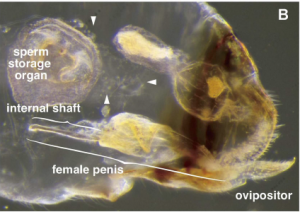

The female reproductive organ.

The authors consider a broad range of factors, but there are two variables that are of central importance. Firstly, the environment that these species inhabit is severely nutrient depleted. Secondly, the semen in question is nutritious and plentiful – if these insects were human size, the amount of semen received by the female during a single copulation would be in the range of 300 milliliters.

In a situation where little food is available there could be considerable selection pressure on females to acquire as much semen as possible. This theory is supported by some of the insects’ unique anatomical characteristics.

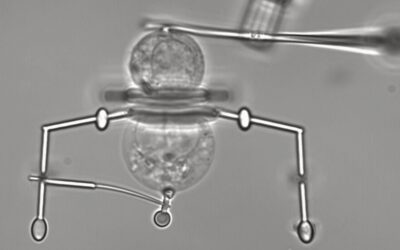

Copulation schematic.

The penises have spines, enabling the female to acquire as much food as possible from unwilling male partners. The mating time is extremely long (40–70 hours), enabling the maximum volume of sperm to be collected. Finally, the females have developed a complex bivalve system that enables them to store multiple deposits of sperm for extended periods.

These anatomical observations, taken together, suggest that competition for nutrition may have played a role in the development of these genitalia.

At this stage the theories on the selection pressures that give rise to these biological structures are purely hypothetical. But work is continuing in order to provide further evidence to support the propositions put forward in this rather compelling essay.