In collaboration with partners from research and industry, ThyssenKrupp AG is initiating a cross-sector technology transfer project focusing on converting process gases from steel production into valuable chemicals. The electricity for this is to come from renewable sources. “The philosophy behind the project is a broad-based, cross-industry approach. A cross-system solution of this kind will deliver better results than today’s already optimized sector-specific solutions. The intention is for the collaboration between the steel and chemical industries to permit cost-effective carbon recycling into fertilizers or fuel. So potentially the project could reduce CO2 emissions from steel mills to virtually zero,” as Dr. Reinhold Achatz Chief Technology Officer at ThyssenKrupp AG, believes.

Professor Robert Schlögl, Director of the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Energy Conversion: “The mission of our institute is to research the fundamental chemical processes involved in energy conversion and thus contribute to the development of new and more efficient catalysts.” Prof. Eckhard Weidner, head of the Fraunhofer Institute for Environmental, Safety, and Energy Technology, says: “Our task is to put the processes examined in the project to targeted industrial use.”

With its subsidiaries ThyssenKrupp Steel Europe, Germany’s biggest steelmaker, and ThyssenKrupp Uhde, engineering company for chemical, refinery and other industrial plants, and with the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Energy Conversion in Mülheim, ThyssenKrupp AG has already carried out planning and preliminary research in a joint preparatory project.

Interest from potential partners is high: Around 40 representatives from research organizations, universities and companies gathered in Duisburg in December 2013 to launch the project. In addition to the Fraunhofer and Max Planck societies, the group includes Ruhr University Bochum, the University of Duisburg-Essen, and the Duisburg-based Fuel Cell Research Center ZBT. Alongside ThyssenKrupp, the industrial partners involved from the start are BASF, Bayer, RWE and Siemens. The group is open to further members.

If the project is successful, in roughly ten years CO2 will be a valuable raw material and will have a significantly lower impact on the climate. Moreover, it would then be possible to use surplus renewable energies directly in the manufacture of industrial products, creating a new network between the steelmaking, power generation and chemical industries.

“Bayer MaterialScience has already demonstrated that CO2 can be a viable alternative for the sustainable production of plastics,” says Dr. Tony van Osselaer, head of Industrial Operations. “That’s a start. Now it’s up to industry, science and government to build on this momentum and drive the broad-based use of CO2 as a chemical raw material.” Prof. Rolf Hellinger, head of Power & Energy Technologies at Siemens Corporate Technology, adds: “The collaboratively developed conversion processes for industrial waste gases will be an important element of future sustainable energy systems.”

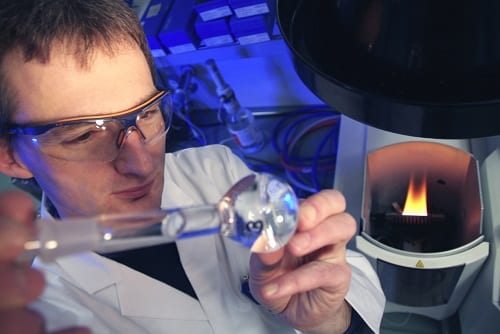

The prospects for the project are good, as the basic chemical processes and required technologies are already largely known. The aim of the project is to clarify important practical issues such as the durability of catalysts, the purification of gas streams, and efficient process control. Converting process gases from steel mills into ammonia for use in the production of fertilizers is already technically possible, though not yet commercially viable. This process would recycle part of the CO2 contained in the steel mill gases. Another possibility would be to produce methanol from steel mill gas, a process in which the CO2 content could be almost completely re-used.

The use of renewable energies for chemical conversion would require catalysts capable of handling large fluctuations in the process. This is an area where more research and development work is necessary. A further challenge: Converting all the CO2 contained in the steel mill gas requires large amounts of additional hydrogen. This calls for the development of new, cost-efficient methods of producing hydrogen that can operate even with a sharply fluctuating energy supply.